THE OTHER RACQUET SPORTS

The following is a chapter from a 1978 book by Richard Squires titled The Other Racquet Sports. For those of us who are enthusiasts of racquet sports in general, it was a really interesting survey of all the other racquet sports written in the wake of the huge rise in popularity of tennis during the 1970's. This chapter tells the fascinating story of how the author, a journeyman athlete who played several racquet sports at the national championship level, convinced the U.S. Olympic Committee to allow him to lead a team in participating in the 1968 Mexico City Olympics in one of the "demonstration sports" chosen by the host country for unofficial competition. This was remarkable in that neither he, nor any of the individuals he would proceed to take into competition had ever before played the games in question: fronton games such as paleta and frontenis. The author passed away November 12, 2003.

Although the saga that follows took place ten years ago, I have included it in this book because pelota is one of the oldest of all "walled" games, and my experience with it was certainly one of the most memorable of my athletic career. - Richard Squires, 1978

It was one of those rare, clear, cool August days in Manhattan as I bounded down the stairs, two steps at a time, of the United States Olympic House. I had to pinch myself to be sure I was not dreaming.

Moments before, in the mahogany-panelled offices of the Director, I had signed an official-looking document granting me complete authority to select, train, and lead, as captain, a U.S. delegation to compete in the 1968 Olympics at Mexico City.

For over a year I had been pleading with, badgering, and cajoling various individuals on the esteemed U.S. Olympic Committe to permit me to put together a team that would represent our country in fronton games - a class of sports that few, if any, Americans had ever played. But just when it seemed that all avenues had been exhausted, one influential director agreed to support my efforts. He sliced through a good deal of red tape (no easy task with anything that involves the sacrosanct Olympics) and finally obtained begrudging approval from the other officials at Olympic House.

What made it possible for me to even dream up this caper was a little-known Olympic tradition. The host country for any Olympics can select two "exhibition" competitions to be held in conjunction with the games. These special events are "unofficial" in the sense that they don't count for anything in the final team standings and don't bestow gold, silver, and bronze medals on their participants. The host country must consider certain criteria when choosing the two sports for these special events. The first sport must be one that in time could become an official part of the Olympics - a minimum of twenty-one countries must be able to field a team. For the second sport, the host country should believe that its team is the best in the world, and in a sense, the host challenges any and all countries to try to dethrone it. Mexico chose regular tennis in the first category and various forms of fronton games in the second.

As I marched up Park Avenue away from Olympic House, I began to think about what I had just done. All I knew about fronton sports was that frontenis, one form of fronton activity, was played with a racquet and a ball. What kind of racquet I couldn't say, and certainly the ball was a mystery to me. I did have the vague notion that a fronton was actually the court, but as to its dimensions, the number of points in a game or match, or for that matter even how one went about winning a point, I was in the dark.

In other words, I had just been designated the titular head of a delegation (not yet chosen) that was to represent the United States in a sport about which I knew absolutely nothing! In slightly less than six weeks, my "team" would be vying against athletes who'd played the game since they were youngsters. In retrospect, I am quite appalled by my chutzpah.

Before anyone is given the wrong impression, let me state emphatically that I am not a scheming con artist. For some twenty-five years I had competed locally, nationally, and internationally in several racquet sports, and in my time I'd been fortunate enough to have won a few major tournaments. Of course, these were all in doubles events, but at the very least this was a tribute to my ability to select strong partners, and my success led me to believe I could pick a team that would learn frontenis quickly and well enough to make a good showing. Or so my rather frantic thoughts ran. Now that I had actually been given the go-ahead, I was filled with some anxious doubts.

Arriving home that evening, I found a cable from the Mexican Fronton Federation. Apparently, the U.S. Olympic Committee had wired the Mexicans to say that the Estados Unidos would be represented in the special event. The cable to me expressed the Mexican Association's appreciation for our interest in the game, and it informed me the Secretary was flying to New York from Mexico that evening in order to have breakfast with me the following morning.

The next day, as I sat across the table from him, I fidgeted with my food and yearned for a cigarette. My appetite had deserted me, and I certainly couldn't smoke if I wanted him to believe that we were training seriously for the upcoming event. During the conversation, he kept using Spanish terms. I could only assume they were somehow related to frontenis, so I kept nodding as though I understood exactly what he meant. Looking back, I recall the one-sided conversation as if it were funny, but I'm sure that at the time I felt as if I were being tortured.

The Secretary asked for the names of the other team members, and about their athletic backgrounds and past performance records in fronton competition. He also wanted to watch us play during one of our practice sessions. Fortunately, it happened to be a Friday, and I quickly informed him that the entire squad always headed out to the country to work out on weekends. I did not think it advisable to let him know that as of the moment I was the entire team.

I was quite relieved when we downed our last cups of coffee, and pleased that my subterfuge seemed to work on the Secretary. But I could have been wrong. His amused smile suggested he knew what I was up to, and so did his parting words: "Just as soon as I return to Mexico, I will send you some instructional information and rules concerning frontenis. You and your teammates might find them helpful."

Over that weekend I telephoned some friends to ask if they would be interested in being on the team. All of them were competent, versatile racquet-wielders, and without exception their initial reaction was the same. They started laughing. But when they regained their composure and realized I was not kidding or drinking, they became equally serious.

We all met the next week in New York and began our workouts at the Racquet and Tennis Club on a four-walled, hard-rackets court. This oversized squash court was better than nothing, but not much better. For one thing, we were told somewhat later that the frontons in Mexico had only three walls. And then there was the problem of equipment.

One of the members of the newly formed team cabled some of his Mexican friends to airmail racquets and balls to us. He told a little white lie by informing them our equipment supply was running low. The truth of the matter was that we did not have any proper racquets or balls.

As the days raced by I sensed an interesting change of attitude in myself and in the other players. A profound and real sense of pride was replacing our initial feeling - that the trip was merely a lark. Perhaps it was the magical word "Olympics" that caused this transformation: we were representing the United States, and not just off on some stunt. Or maybe it was just each individual's sense of personal (rather than national) pride. Whatever caused the change, we all felt it undeniably.

As the fateful day drew closer, we all became more serious about training rules and practice sessions. The smokers quit smoking and began jogging each morning before work, and all of us tried some calisthenics in our offices. And a few even made the supreme sacrifice - they gave up the second martini.

Because we were competing in a non-official sport, we could not wear the official U.S. Olympic uniform. Undaunted, we came up with our own outfits: blue blazers, gray slacks, black loafers, and white turtleneck shirts. Business firms donated the clothing, racquets, jewelry, and so on, and I must admit our appearance was damned natty. Even if we were only borderline, quasi-Olympians, we would certainly have won any medal they might have given for "Best Dressed."

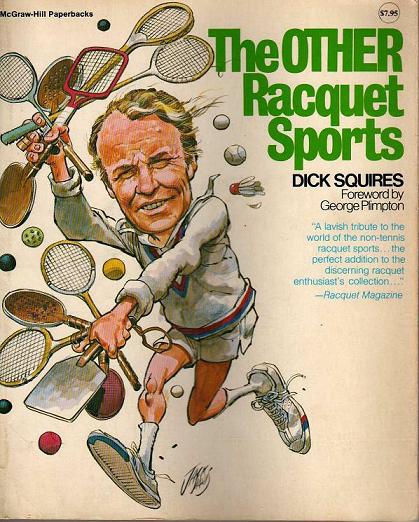

The national press and television networks were quick to pick up on our story. A front-page article in the Wall Street Journal intimated throughout that the somewhat aged U.S. Olympic Fronton Team represented living proof that anyone could compete in the Olympics. We also appeared bright and early one morning on the Today show. The producers had scheduled an interview of seven minutes for us, but Hugh Downs, the host, became so fascinated with our story that we stayed on for the entire first half-hour segment. In addition, we were the subject of a five-minute documentary shown on Roger Mudd's Saturday Night News. Narrated by Heywood Hale Broun, the film showed us sitting at our desks "looking busy", then at 5 P.M. picking up our briefcases and heading outdoors. The next scene had us jogging up Park Avenue, against the tide of homeward-bound commuters, until we arrived at the Racquet and Tennis Club for our daily workout. Subsequently a camera crew followed our activities in Mexico, filming a few of our all-too-brief encounters.

The average age of the team members was thirty-seven, which by almost any sport's standard is well into an athlete's twilight years. One team member was forty-seven, and he dubbed himself the "world's oldest living Olympian." In Mexico, he played in a doubles match in which the opposition's combined ages totalled less than his!

On the morning of October 9, our twelve-man squad boarded an Eastern Airlines jet for the trip to Mexico City. From the stories in the Mexican newspapers it seemed that a civil war was going on. We'd heard that army tanks had entered the University of Mexico's campus in an effort to drive out the revolutionary students. A cordon of armed militiamen moved in behind the tanks, and there had been some machine-gunning. We wondered if we were all slightly crazy to be deliberately heading down to Mexico at all. (That identical thought had been on my mind for the past six weeks, but for different reasons!)

The jolting thud of wheels retracting into the belly of the aircraft signaled it was too late to turn back. We were really on our way to play in the Olympics, and physically and mentally the team was as well prepared as it ever was going to be. Besides, we still had a week before the actual competition began, which gave us time to "master" the games.

I fell asleep to the steady whine of the plane's engines and dreamt that the United States had won the Olympic Frontenis title. What a story it would make: "Competing for the first time in fronton games, the U.S. team, after only a few weeks of familiarizing themselves with the sport, blasted their way to the crown. A testimonial to their all-around racquet versatility is to be found in the astounding fact that prior to the Olympics no one on the squad had even seen a fronton or even knew how to keep score."

I awoke with a start when our plane hit an air pocket and plummeted sickeningly before safely heading off. The incident brought back to mind a macabre comment made to me the previous week: "You mean the entire U.S. Olympic Fronton Team is flying together? Suppose the damn plane should crash? It would set back frontenis in America one whole day!"

After our national publicity I had received several letters from individuals who had played frontenis and wanted to be included on the squad. It was too late, though - the uniforms had already been ordered. Also, we did not want any last-minute "strangers" on the team, especially if they knew how to play the game. Their presence would destroy our image.

Upon our arrival in Mexico, it did not take us long to discover that frontenis was far different from any game we'd practiced, let alone ever played. The three-walled cement court, known as a fronton, is usually 110 to 125 feet long and 36 feet wide. Its walls are 30 feet high. As one faces the front wall, there is an open area (without a wall) to the right. A boundary line on the floor on the right side extends the entire length of the court, and the ball must always bounce within it. In other words, balls landing to the right of that line are out of court.

The fronton also has lines on the front wall and the floor, between which served balls must land. And at the base of the front wall is a 36-inch-high metal plate, or "tin," that spans the width of the court. All shots must eventually be returned to the front wall and land above this 3-foot-high strip to be considered still in play. (Hitting the metal strip is tantamount to hitting the ball into the net in tennis or striking the telltale in squash; you lose the point.)

The ball must always be returned to the front wall before it bounces twice on the playing deck. A wide variety of angled shots can be made off the back wall and side wall, and shots to the front can be strategically placed out of reach of the opponents - if you know what you are doing, that is!

The frontenis racquet is a reinforced tennis frame strung loosely with very think nylon. The yellow rubber ball is approximately the size of a golf ball, and it must be the fastest rubber ball ever devised by any sporting-goods manufacturer.

In many racquet sports, the majority of shots are executed by making contact with ball at or below knee level. With the much livelier frontenis ball, however, most strokes are hit at chest or even shoulder height. It was, needless to say, an awkward and difficult swing for all of us to grasp.

Probably 80 percent of all the extended rallies occur up and down the long, left-side wall, and experienced players try to make the ball cling as close as possible to that wall. Trying to "pick off" a pellet travelling at about 180 miles an hour along the wall is no easy task, and frequent errors are therefore commonplace. Another winning shot can be made by slicing the ball high into the left-side wall. If properly placed, it rebounds at a sharp angle into the front wall, bounces high off the floor, and kicks sharply to the right in the direction of the open area - into the heavy screening separating the court from the spectators. Unless this shot is intercepted by an opposing player who is covering the front part of the court it will almost immediately sail out of reach. (The partner in the back has little chance of getting to the ball before either it or he smashes into the thick, chain-link fencing.) Deftly stroked drop shots and soft corner shots are not too effective because of the speed and liveliness of the ball.

Only doubles was played in Mexico. A doubles team consists of one partner playing up toward the front of the court and the other covering the rear. Usually, the front man is the person with the faster reflexes, which permit him to cut off many of the opponents' drives in the fore court. He also must have the ability to start quickly in practically any direction. The back man is the strong-armed, steady player on the team. He can keep sending the ball back to and high up on the front wall. He should possess an inordinate amount of stamina and patience, as he normally hits 75 percent of the shots. (El Capitan Squires played the front position in his matches - not necessarily because of his lightning-like reflexes and speed of foot, but rather due to the somewhat poor condition of his legs and lungs.)

A complete match is just one game totalling 30 points. When two evenly matched teams are competing, the rallies are often quite lengthy, and a match can last as long as 90 minutes.

The Mexicans, who claimed to be the best in the world in this sport, were absolutely wonderful to their North American cousins. Their top team and coaches worked out with us at least twice a day prior to the start of the actual competition. They were extremely pleased the United States had taken a sincere interest in their game, and they believed our presence added a good deal of prestige to the event. And it didn't take them long to realize we did not have the slightest notion as to how to play the game. Undoubtedly, they did not feel that we could in any way jeopardize their self-claimed world supremacy.

Well, the "impossible dream" did, indeed, turn out to be impossible. Despite the expert instruction we received from the Mexicans, we quite decisively lost all our matches. Our Mexican friends "carried" us during the opening match, allowing us to win 16 points. Immediately after the contest, the President of the Mexican Federation of Fronton, Señor Jorge Ugalde, announced to the fans in the bleachers that the competitors from the Estados Unidos had only played the game for a few weeks and didn't have a fronton in the U.S., but they had, in his words, "shown a lot of courage, grace, and agility." I was not certain if he truly meant his highly complimentary remarks, or whether he merely felt embarrassed for us. In either case, my teammates and I were grateful.

In any event, our secret was out, and from then on for all the remaining matches we were the "darlings" of the Mexican frontenis crowds. They loved the struggling "gringo" underdogs and loudly supported and encouraged us in our subsequent games against Argentina, Spain, France, and Uruguay. With the umost bravado they wildly applauded our opponents' errors and screamed "Olé" when a lucky winner caromed mistakenly off the wooden part of our racquet frames.

After the close of the Olympic games and four days in Acapulco to "unwind" from the pressure of the competition, we flew home feeling quite proud of ourselves. We had made many friends and had taken our defeats graciously. All of the lasting thrills of being Olympians were ours for a lifetime, and we had them without having to go through the rigors of the strenuous training normally associated with such an athletic endeavor.

We felt our trip to Mexico was a Walter Mitty dream come tru. George Plimpton had nothing on us. Everyone on the team believed the trip was a once-in-a-lifetime experience, and we would now be content to grow old gracefully. We all had a marvelous story with which to regale our grandchildren: "Yes, I was an Olympian way back in 1968 at Mexico. Although we weren't too familiar with the game of frontenis, our natural abilities took us all the way to the finals before we ran up against the Mexican champions and then..." Such tales have a way of getting better as the years pass by.

Upon returning, we did in fact have a great deal of fun telling our envious friends all about the trip. Naturally, we were subjected to some good-natured needling, and the fact that we had been beaten by every country left us open to some stronger criticism. People asked why we hadn't selected better and younger athletes? Why weren't there any try-outs? We reminded these critics that the total elapsed time from when I received the official sanction from the U.S. Olympic Committee until we were actually initiated on a fronton was a mere six weeks.

We were all sustained, however, by the rationalizing phrase of Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the Modern Olympic games: "Competing is more important than winning; as in life the challenge counts more than the triumph." The U.S. Olympic Fronton Team of 1968 competed and met the challenge with "courage, grace, and agility."

Memories of Mexico and our Olympian Odyssey had all but faded into oblivion when I received an invitation from the International Federation of Pelota Vasca to compete in the even more prestigious World's Championships, which were to be played in September of 1970 at San Sebastian, Spain, the cradle of these fronton games. It had been almost two years since any of us had held a frontenis racquet in his hand, and one of the members of the squad even had to unscrew his racquet from the wall in his playroom in order to have equipment for Spain.

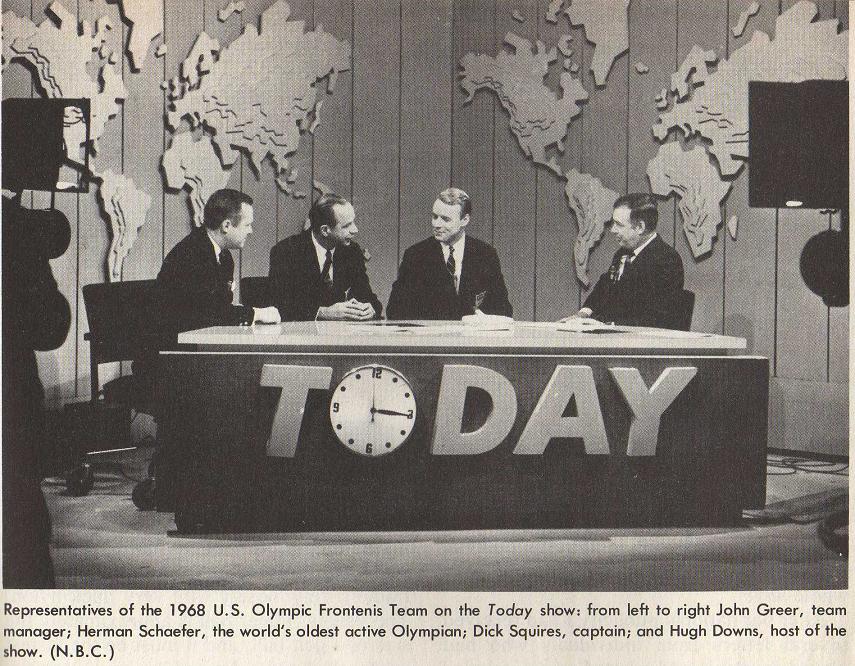

After several meetings and much debate among the "veterans," we agreed to form the U.S. Fronton Athletic Association, which made us sound quite expert, influential, and national in scope. We decided to send a team to Spain to represent the United States again. A few of the original frontenists, for one reason or another, could not make the trip, but their places were filled by avid "rookies" eager for their share of fame and glory.

We departed from New York's John F. Kennedy International Airport on September 12. This time, in contrast to two years before, the entire team was very relaxed. No one had bothered with early morning jogging or push-ups and sit-ups in his office. We were all two years older and a good deal wiser. Gone were the ambitious aspirations of annexing the world title. We now knew our chances of beating any country at its own sport were somewhat less than slim. We were in it just for the opportunity to have another "once-in-a-lifetime" experience.

Upon arriving in the picturesque resort town of San Sebastian, located on the northern coast of Spain at the foot of the Pyrenees, we were surprised to discover there were few frontons in the city. The indoor fronton to be used for the championship matches, called the Anoeta, was still undergoing the final stages of remodeling and painting - just a few days before the games were scheduled to begin.

Fortunately we discovered an oversized fronton on the grounds of a 300-year-old convent and, after some difficulty, were able to convince the Mother Superior to allow us to work out on it twice a day. The convent was a strange combination of a nursing home for the elderly as well as a nursery for young orphans. Each day, upon our arrival for practice, we were closely followed by an entourage of curious children who must have been awed at the sight of our crisp white playing togs and the shiny gold seal of the United States Fronton Athletic Association emblazoned on our fancy jackets.

The wizened custodian of the ancient building that housed the fronton took overt glee in supplying us with an abundant amount of wine and beer - San Sebastian's traditional beverage for quenching one's thirst during (not after) an athletic event. Not a bad custom! We rationalized such an unusual training regimen by convincing ourselves it was probably safer to indulge in the spirits than to drink the local water. By the end of our relaxed two-hour workouts it was difficult if not impossible to know how well we were getting accustomed to the lively bounce of the pelota (ball).

Our evenings were spent at the plush Hotel Monte Igueldo, situated high up on the side of a mountain overlooking the blue, clear, and calm waters of San Sebastian Bay. Our team manager would entertain us in the hotel's small cocktail lounge. Obviously we were not in a place conducive to maintaining a spartan atmosphere of training, and the battle cry of the 1970 U.S. Fronton Team inevitably became "con hielo!" - meaning "with ice!" Our manager would order his "hits" (double vodka martinis) and amuse us for many happy hours. By dinner time, which in Spain is usually around eleven at night, we would all be pretty under the weather, and all too often it was 2 A.M. before we laid our weary and stiff bodies down to rest for what remained of the night.

All members of the squad were very compatible with one another. Not only did the varying personalities blend beautifully, but we had a genuine sense of pride at just being members of this rather unusual team. At the time I felt we could have travelled and lived together for a year or more without there ever being tense moments or clashes.

The five days of practice raced by and the Campeonato del Mundo de Pelota (Championships of the World in Ball Games) were ready to commence. The official opening ceremonies were staged the evening before the actual competition. Generalissimo Franco attended this event, sitting, we found out later, on a pillow in order to seem taller to his subjects. From his flag-bedecked royal box he smiled down on us, and he was surrounded by dozens of sober-looking military guardsmen equipped with submachine guns.

The athletes from the various countries paraded in at the appointed hour and stood at attention on the fronton floor, facing the full gallery of enthusiastic spectators. A band played each country's national anthem, and as the "Star Spangled Banner" resounded throughout the arena, my eyes moistened. Not only was I proud to be representing my country, but tomorrow we would be performing before a gallery of several thousand aficionados and a television audience of approximately 15 million Spaniards. The thought was overwhelming. I only hoped we wouldn't be terribly outclassed.

This moment of mixed emotions just as quickly gave way to horror. When Spain's national anthem had ended and the president of the International Federation of Pelota Vasca was about to address the audience, a Basque man jumped up onto the ledge of the upper gallery, yelled something ("Free the Basque provinces!") in the direction of Franco, ignited his gasoline-soaked clothing, and plunged head first to the floor below. He landed in an aisle practically on top of a group of panic-stricken spectators and then staggered toward the playing area. There he collapsed in a fiery, smoldering heap no more than 10 feet away from our delegation. He lay there, spread-eagled and not moving, and no one in the horrified crowd moved to extinguish the swirling flames completely engulfing him.

A lovely woman whose brown hair had caught on fire when the martyr charged into her raced wildly out onto the court in the direction of our now-scattered team. Her eyes showed terror as the flames crackled through her hair. Fortunately, one cool member of the U.S. team tore off his blazer, wrapped it tightly about her head, and smothered the flames. Later we were informed the woman was going to be all right and would not have any disfiguring facial burns. The fast-thinking, heroic act by the Americano was mentioned in the press the following morning.

The fire on the now motionless and mercifully unconscious man was finally put out, and he was dragged feet-first out of the arena.

Pedro Bacallao was my partner for the opening frontenis match against Spain. Still shaken by what we'd seen, we managed to keep our two-year losing streak intact by succumbing easily, 35-19. (For the world's championship, the officials had raised the winning score from 30 to 35.) Again, as had been the case in Mexico, in attempting to win points we tried to hit too many risky winners and consequently made many costly and foolish errors. The following morning's papers were kind to us, however. They stated that while we were inexperienced we showed some "style and spirit," and this rather cryptic phrase gave us a little satisfaction.

Paleta, another form of fronton sport, was also an event at the Championships. The game is played with a heavy, oval-faced wooden paddle instead of a strung racquet, and it is even more difficult to play than frontenis because of the smallness of the paddle and the extreme speed of the ball. Our paleta players were scheduled to play an Argentinean team the same day, but none of the officials had told us of a last-minute change in the rules. In Mexico, the paleta service had to bounce in a prescribed area between two lines located approximately in the center of the court. The Spanish officials, however, decided that for this championship the serve could be hit anywhere, as long as it landed within the playing area of the fronton. The U.S. Paleta doubles team, in other words, walked out onto the fronton to compete in a World's Championship match with absolutely no idea as to how to return a service that landed in the extreme rear portion of the court.

Unfortunately for us, Argentina won the toss of the peseta and decided to serve the pelota first. Our back man did not come within six feet of the first four deliveries as the ball ricocheted high and deep off the side and back walls. I was observing the slaughter from a seat way in the back of the arena, as near as possible to an exit. At first the knowledgeable (and paying) spectators shifted restlessly in their seats, seeming to share the embarrassment our boys were feeling. But as the score quickly mounted to 12-0 with hardly a rally, some of the more ardent and vocal fans began to giggle and eventually whistle to show their dissatisfaction with the play - or lack of it.

One of our squad's "rookies," a young man who was scheduled to compete in a paleta match the subsequent day, was sitting directly in front of me watching the debacle. He had, throughout our training, immensely enjoyed all the benefits he received as a member of the 1970 U.S. Fronton Team, and on several different occasions since our arrival he had profusely thanked me for including him on the squad. Now, however, he was witnessing what would undoubtedly be his fate the following day. The rehearsals were over, and spotlight would soon be on him. The moment of truth was imminent, and he did not like what he was seeing. Suddenly he wheeled around and stared right into my eyes. "Squires!" he hissed, with all the contempt and scorn he could muster.

Meanwhile, our manager stood passively in the rear of the court watching the proceedings with an out-of-character grim expression on his face. He looked very official, however, in his sweater with the red and blue striped V-neck and his white slacks. The gallery's catcalls grew ever louder as the Argentinians continued their hard-driving, deep serves. At 16-0 our back man, flushed from embarrassment and exasperation, tripped over a television cable lying outside the playing area as he vainly tried to return a sharply angled ball off the rear wall. He fell heavily to the hard cement floor, and the spectators guffawed cruelly.

Our manager slowly removed the dark glasses he wore to protect his bloodshot eyes, the result of the previous evenings of entertainment, and turned and ambled slowly in the direction of the screen that separated the fronton from the gallery seats. I thought he was going to leave the court, but instead he stopped short of the exit door and peered through the heavy mesh at the stands, looking for a familiar face. Seeing us, he cupped his hands and loudly yelled, "I need a hit!"

As in Mexico, what made me so proud of the entire team was that no matter how badly any of us was being drubbed, no one ever showed any inclination to give up or to conduct himself in an unsportsmanlike manner. And we were all individuals who had become fairly accustomed to winning in other athletic pursuits.

The following day I had to leave the team and go to England on business. My plane did not depart until mid-afternoon, however, so I designated John Halpern and myself to be the next "lambs" in the morning frontenis match against France. (The French had beaten us in Mexico 30-14.)

Throughout breakfast and on the way to the Anoeta, John and I discussed strategy. We decided we had absolutely nothing to lose (except the match) and everything to win by just keeping the ball in play. We were not going to try any fancy shots, but just attempt to return the ball high on the front wall. At the very least, we would win more playing time than usual on the fronton!

The stands at the arena were packed with an unusual number of people attired in their fanciest Sunday finery. This match, too, was to be played before a television audience. The very thought was enough to make me want to catch an earlier plane!

As we slowly dressed my heart was pounding with excitement. The small locker room was located directly behind the fronton, and as we doffed our city clothes and donned our playing togs, we could hear the sporadic applause and cheers accompanying the match in progress. My mouth was chalky, and I could barely tie the laces on my sneakers. John was quiet and somewhat testy. We carefully avoided our French adversaries, who naturally seemed quite confident as they prepared for their "gimme" match against the notoriously inept Americans.

Prolonged applause from outside informed us the match had ended. We were up next. Before entering the fronton for our warm-up session, John and I exchanged clammy handshakes and admonished each other simultaneously, "Remember, no shots!"

The French players did not look that tough as they hit their practice shots. But then again we had on many occasions in Mexico held the same impression of other opponents who'd gone on to baffle us completely with their unorthodox strokes. The two Frenchmen weren't particularly friendly, and they shunned conversation with us as we smacked the ball around the court. I couldn't understand why they thought they had to psych us. They appeared to be in their early twenties, while John and I had a combined age of seventy-four.

All too soon the officials called an end to the warm-up period. As is the tradition at the start of all matches, we lined up, paraded single file to the center of the fronton, and bowed to the patrons in the stands. Long blue sashes were ceremoniously wrapped around each of our waists, and red ones were wrapped around the French players. These bands signified to the gallery the pairing of partners. The French won the toss (we were already in trouble) and started serving.

I cut off the first serve, which fell rather shallow in the court, and had all the intentions of smashing a high, safe backhand down the left side wall. But by mistake, the ball hit off the side wall first, rebounded in a flash off the front, bounced on the floor, and streaked like an errant bullet out into the protective screening for a winning placement! It happened so unexpectedly that the opposing front man just stood there looking dumbfounded. To the accompaniment of resounding cheers, I picked up the ball, shrugged nonchalantly at the opponents, winked at John, and went back to serve with the United States team way out front, 1-0.

Still feeling jittery, I was not at all sure I could fully raise the racquet over my head; consequently, my service was far shorter than I planned. The ball, however, hit the side wall on its way back and caromed sharply right at the feet of my French counterpart. He jumped high, swung wildly, and completely missed the ball! An ace! We stormed ahead to 2-0!

It was apparent from the spontaneous reaction of the predominantly Spanish crowd that they were supporting us. I, of course, wanted to believe it was our good looks and natural charisma, but I suspect it was primarily due to their ill feeling for our rivals. (There is little love lost between the Spanish and the French.) In addition, the sight and sounds of our teammates and Mexican mentors madly cheering in the stands must have been contagious. The arena sounded like a crowd attending a deadlocked hockey game in the closing minutes of the third period.

At 6-3 I went back to serve again. John strolled over and whispered, "Hey, you know what? We're twice as good as they are!"

It did not take us long to realize that their front man was not as strong as his partner, so we did our best to play the majority of shots right at him. This strategy seemed to unnerve him, and we continued to pile up points at his expense.

Midway through the match, I gazed up at the electric scoreboard, which showed us ahead 18-10, and a terrifying thought suddenly struck me: "My God! We have a chance of winning our first match ever, and against a country that practically invented the sport!" It did not seem possible that we could continue our winning ways. The remaining 17 points we had to win might as well have been 170. I feared the whole scene was unreal - that it was another dream, and we would soon be rudely awakened and have to play the match all over again.

At one point another evil thought entered my head. Suppose the cocky French players were intentionally holding back - purposely letting us get ahead so they could break our hearts by pouring it on for an exciting come-from-behind victory over the giant, wealthy, United States.

At 25-14, however, we began feeling for the first time that maybe, just maybe, we were doing something right. There was just one rather serious problem that had to be overcome - our lack of stamina. The peculiar training program of the last several days (or the last twenty-five years) was beginning to catch up with us. I glanced back at John. He was breathing hard and perspiration completely saturated his once immaculate tennis shirt. We won the next point and decided to take a one-minute rest period.

During this fleeting intermission we discussed exactly what we had to do. I told John he was playing superbly, to keep it up, and that I would do everything I could to help him out. Trying to catch his breath he gasped, "Okay, but for Chrissakes, no shots!"

A few moments later we led 29-16. Pandemonium had broken out in the arena. At the time I thought the shot John had just hit out of reach of the French back-court player was a good one, but hardly worthy of such an overwhelming reaction from the spectators. After all, we still had 6 points to win before taking the match. Through the heavy mesh fencing I saw Pedro Bacallao frantically beckoning me to come over to the screen. I could hardly hear what he was yelling above the din. Finally his words became audible: "Only one more point! Just one more point and we ween!"

I screamed back, surprised at my own anger, "Sit down, you fat Cuban! This is not Mexico. They've changed the number of points to 35. Remember?"

Other members of the team surged forward to confirm Pedro's excited comment. Apparently, at a special meeting of the Federation held the previous evening the officials had decided to employ for all remaining matches the same scoring for frontenis as had been used in Mexico; that is, 30 points ended a match. Again, no one had mentioned this change to the players.

We were, therefore, at match point! It has often been said that the most difficult point to win in the whole world of racquet sports is the last one. Strange things - usually against you - happen at this critical stage of any contest. Broken racquet strings, bad bounces off the playing surface, twisted ankles, a lob lost in the sunlight, leg cramps, a sudden breeze that carries an apparent winner just beyond the baseline, a lucky net cord off the opponent's racquet, a string of inexplicable errors off your racquet, a sneeze from a spectator that shatters your concentration and timing on an easy overhead, and, of course, the elbow.

For a split second I was amused by the fact we were playing in a World's Championship match and did not even know how many points we had to win in order to defeat the opposing team. But then again we had never been on the verge of a victory before. Our main goal in Mexico was only to try and win enough points to put our scoring in the double-digit column. Usually we had to settle for anywhere from 4 to 9 points. When we were able to win 10 or more points, we considered it a moral victory.

The next rally was an extended one, and the Frenchmen were battling for their lives. They made two unbelievable retrievals of shots I felt would mean the match for us, and went on to win the point. The red numerals on the scoreboard switched to 17.

I was as physically and emotionally spent as a marathon runner during that last mile. The racquet in my hand felt as though it weighed 50 pounds. The opponents made note of my condition (or lack of it) and fired a rocket-like service directly at me. I decided to go for a desperate, outright winner. Making impact with the speeding ball before it hit the floor, I swung with all my might, intending to ram it low along the side wall. My timing was way off, however, and the ball slammed loudly and abruptly into the tin. Another point for France, 29-18. If John's gaze could kill, I would have met an instant death. "No shots!" he seethed at me.

Our adversaries seemed to sense they were still alive. During the next lengthy exchange of shots they made some more startling "gets" and won their third consecutive point under pressure. The red-and-blue scoreboard flashed 29-19.

"Godammit! Why can't we win just one more point? Even if it's a miracle shot off the wood, we'll take it," I muttered to myself.

And that's exactly what happened on the next point... but off our opponent's racquet. I had maneuvered my man way out of position and laced a scorching side-front corner shot that appeared to be far beyond his reach. The back man had no chance to get to the ball. But when I was about ready to run and give John a big victory kiss, the French front man made a flying lunge in a frantic effort to retrieve my shot. Somehow he caught the ball on the top of his racquet frame, and it rebounded off the wood and floated lazily toward the corner of the front wall. I was frozen in mesmerized amazement. His ball hit gently directly into the corner no more than an inch above the tin and immediately died - an unbelievable, impossible return!

The score was 29-20, and the spacious fronton suddenly seemed both terribly small and large. The French appeared to be able to cover every shot we hit, whereas our legs trembled with fatigue. Was it possible we were going to blow the one chance we had to win our first victory in a World Fronton Championship?

Frontenis is similar to all racquet sports in that it is a game of momentum. It is not uncommon for a team to win 10 or 15 points in a row, even when the competitors are evenly matched. A sickening, inward fear that we never were going to win the last elusive point swept over me. My nerves were beginning to get to me, and I felt the onset of nausea. Our opponents were gaining confidence - everything was working for them.

The following rally seemed to go on endlessly. Everyone was playing with extreme caution, hitting the ball high up front and back down the left side wall. The tension in the arena was heightened by the absolute silence of the gallery as they intently viewed the struggle. The only noise to be heard was the resounding clear tone of the small, lively ball as it streaked off the walls and floor and "pinged" off our racquet strings.

After what appeared to be an eternity, John lashed a high, two-handed drive down the backhand side. The ball clung to the wall as if it were magnetized, and the opposing player in the back court made a desperate attempt to pick it off cleanly. But his racquet caught too much of the wall and not enough of the ball, and the yellow pellet fell short of the front wall. The match was ours!

Bedlam broke out in the arena. To the sounds of wild cheering and thunderous, rhythmic applause, John and I dropped our racquets, hugged each other, and jumped up and down and around in circles as though we were on a tandem pogo stick. Our disappointed adversaries could not fully comprehend the ecstatic feelings charging through our weary bodies at that moment. They were unsmiling and stolid as we shook their hands and made the usual perfunctory remarks so often uttered by winners: "Too bad. We were damned lucky. Good game."

Members of the U.S. Fronton team sped out onto the court followed closely by several hundred Spanish fans who had been caught up in the frenzied elation of the whole scene. While we were being squeezed by our teammates, anonymous hands slapped our backs and shoulders. Everyone was screaming with delight.

John and I were hoisted up on people's shoulders and paraded around the entire perimeter of the fronton accompanied by pulsating applause from the jubilant, appreciative audience. I now knew how all football coaches must feel when their teams carry them off the field after a glorious victory over their arch rival.

I have competed in many tense and important matches over a span of twenty-five years and have experienced innumerable spine-tingling moments in my athletic life. But no victory ever meant more to me than that frontenis match in San Sebastian on September 20, 1970. And the fact that it occurred to me at the tender age of thirty-nine only heightened the exaltation.

It was, after all, the very first win - perhaps the last - for the United States in International Fronton Games. The whitewashings in Mexico were totally forgotten with this tasty triumph. Our critics mouths would be sealed forever. This victory also meant the United States Fronton team could no longer be dubbed a farce. How could anyone ever again label us court jesters or pretenders? We had won a major match in the World's Championship! Needless to say, when I flew to England that afternoon, I was soaring at a greater altitude and speed that the B.E.A. jet carrying me.

Unfortunately we lost all our remaining paleta and frontenis matches, but it really did not matter. After all, what does a person do for an encore after just accomplishing the impossible? We had beaten France, and that made us fifth in the world - out of six. Not a bad ranking considering it was achieved by some junior geriatric business and professional men who didn't even have a court - excuse me, a fronton - back home.

So with slight apologies to Monsieur Coubertin, I would like to amend his statement. While competing is more important than winning and, as in life, the challenge does count more than the triumph, I will probably cherish that victory in San Sebastian more than any athletic competition or challenge I will ever undertake again in my lifetime.